welcome to Zim

"Put me first in your book," said Thoko. I don't know how he knew I was writing about my trip, maybe he saw me taking notes on my phone. I told him I would.

Thoko sat in the seat next to me for the Intercape bus from Johannesburg up to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. When I first got on the bus, a woman in the front row turned around to me. "Aren't you on the wrong bus?" she asked. "Bulawayo?" I replied. "Ah, she said, I thought you were going to Cape Town." I couldn't blame her - I was amazed to see a couple other white people on the bus at all. Bulawayo was the halfway stop on my trip from Joburg up to Vic Falls, on the Zimbabwe-Zambia border.

When we were waiting for the bus to take off - delayed 20 mins - I joked to Thoko about running on Joburg time. "BMT!" he said. "Black man's time." Thoko was a grandfather at 50, with 5 kids and a few grandchildren - a typical sub-Saharan African story. He worked as a boilermaker in the Bulawayo mines, having gone to study his trade for a year in London on sponsorship from his company. He told me his dream and life plan was to retire at 55 with a farm in Lusaka, Zambia, where he was raised. There, he would raise pigs and cows and and use the proceeds from his farming to travel.

One year ago, some men got on the same bus we were taking with a gun and told people to hand over their cell phones and wallets. When they got back to Thoko, he noticed something odd about the barrel of their gun - it wasn't thick enough to house regular bullets. It was a pellet gun. He stood up, grabbed the gun and snapped it over his knee. The would-be robbers got the beating of their lives and ended up in the hospital. When Thoko got off the bus, everyone handed him a few dollars as thanks. "Put me in your book," he said.

Scenes from Bulawayo's Railway Museum, the biggest tourist attraction in Bulwayo, and the surprisingly well-done Natural History Museum, which had a couple unnervingly open and empty poisonous snake cages.

The Zimbabwe border crossing went seamlessly - until the immigration officer saw how few pages were left in my woefully small emergency passport. Normally, visitors to the country are meant to have two full blank pages available, to get visas in and out of the country. I had one. It looked like I would be sent back to South Africa without even getting into the country. However, he applied the full-page visa before checking, so he was in a tough spot. After 15 minutes of waiting, I asked "what can I do to help?" He looked at me. "How about you buy me a cup of coffee?" I agreed. We walked outside of the immigration office and I exchanged him $5 for my passport. He laughed, "Welcome to Zim."

Coming in to Zim, our bus was stopped by police blockades four times in the course of a couple hour. Maybe the enhanced security was for the Easter holiday. Maybe it was a chance for the police to make a little extra money. "I know this guy," said Thoko of one of the officers combing through the driver's papers, "He lives in my village. When I see him next I'm going to kick his ass for pulling us over for so long."

The Bulawayo (closed) power station, one of the few large buildings in the city.

Passengers arriving at the station for the overnight northbound train from Bulawayo.

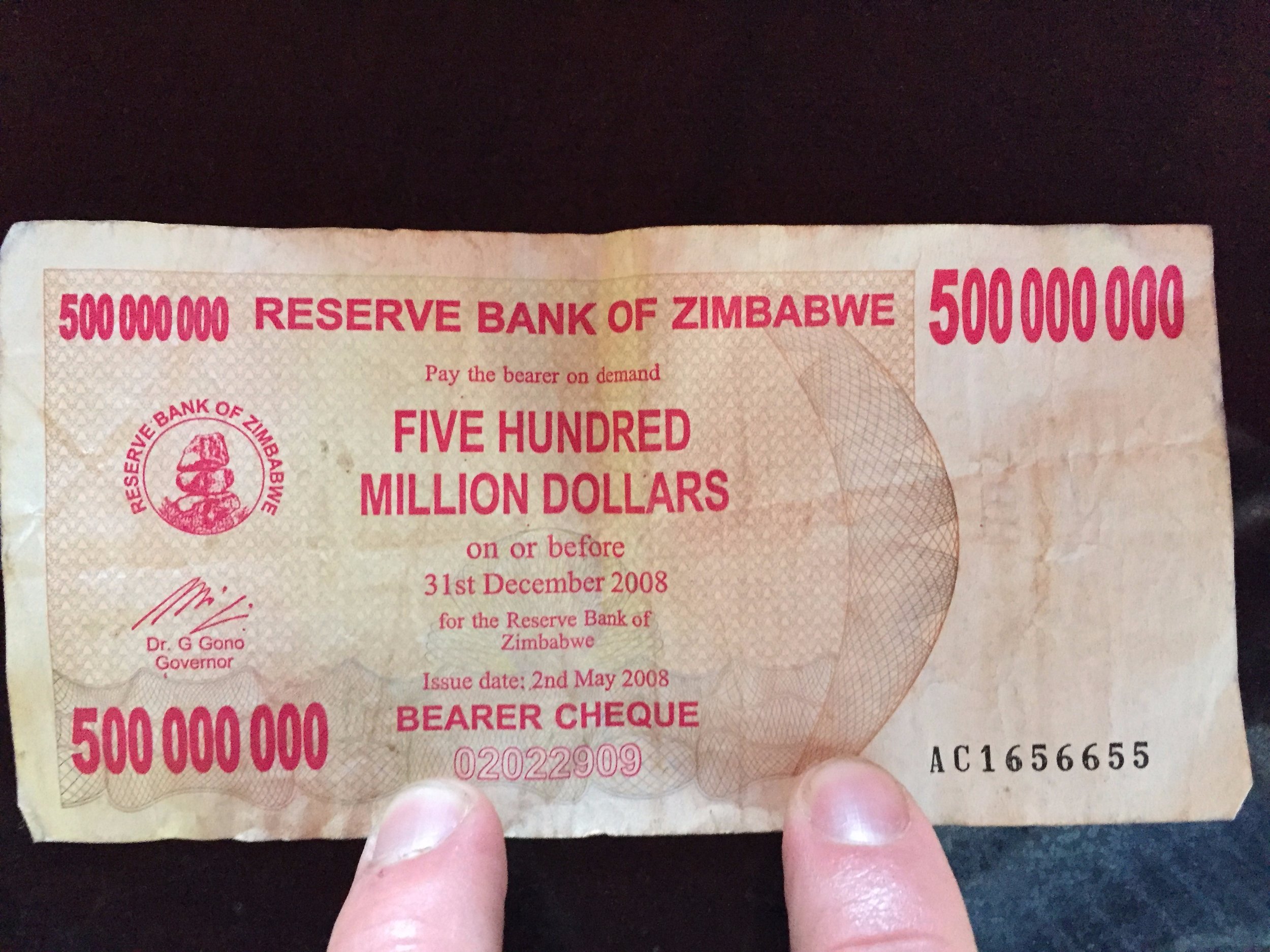

The bus dropped us in downtown Bulawayo, the second-largest city in Zimbabwe after the capital, Harare. Zimbabwe is a world apart even by southern African standards, having endured the one-man rule of president Robert Mugabe (or Uncle Bob, as a Botswanan with whom I shared a border taxi called him) since 1987. Among the other problems caused by his revolutionary rule, built on the founding principles of socialism, African nationalism, and western antagonism, was hyperinflation. The value of the country's currency, Zimbabwe Dollars, was redenominated three times - with the latest denominations in the 100's of trillions. The inflation had run rampant and dragged the country's purchasing power down for decades, so that Zimbabweans now accepted dollars freely as the dominant currency. By differing accounts when I entered Zimbabwe, he was either about to be overthrown or leader for life.

“It’s a one-man problem,” many white Zimbabweans explained to me. Depending on whom I talked to, they said variously, “The president is out of his mind” or “He’s lost it” or “He’s off his chump.” Even the kindly winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Reverend Desmond Tutu, had said, “The man is bonkers.”

The Robert Mugabe rumors, which I dutifully collected, depicted the poor thing as demented as a result of having been tortured in a white-run prison: long periods in solitary, lots of abuse, cattle prods electrifying his privates, and the ultimate insult—his goolies had been crimped. Another rumor had him in an advanced stage of syphilis; his brain was on fire. “He was trained by the Chinese, you know,” many people said. And: “We knew something was up when he started calling himself ‘comrade.’” He had reverted, too—did not make a decision without consulting his witch doctors. His disgust with gays was well known: “They are dogs and should be treated like dogs.” He had banned the standard school exams in Zimbabwe, “to break with the colonial past.” Some rumors were fairly simple: he had a lifelong hatred of whites, and it was his ambition to drive them out of the country. Of the British prime minister he said, “I don’t want him sticking his pink nose in our affairs.”

Noting all this, I kept thinking of what Gertrude Rubadiri had told me: “We called him ‘bookworm.’” Really, there was no deadlier combination than bookworm and megalomaniac. It was, for example, the crazed condition of many novelists and travelers. The long lines I saw at gas stations told part of the story: Zimbabwe had a gasoline shortage. The new $500 million Harare International Airport had run out of aviation fuel. No hard currency meant a severe reduction in imported goods. There had been food riots in Harare. The opposition parties had been persecuted by the ruling party’s goon squads. The unemployment figure had risen to 75 percent, and visitor numbers had dropped by 70 percent.

The irrationality of the president was so well known his accusations had ceased to be quoted in the world’s press, except for his maddest utterances, such as “I have a degree in violence.” Foreign journalists had been attacked, some seriously injured, and others had been deported for trying to cover stories of intimidation and disruption.

“Everything Mugabe says and does is intended to drive the whites away,” a white Zimbabwean told me. I replied that it seemed to me that black Zimbabweans were enduring an equally bad time, with such high unemployment, high inflation, unstable currency, and an economy in ruins. Blacks were being driven away too—many had fled to South Africa.

- Paul Theroux, Dark Star Safari

Walking around Bulawayo, it was easy to see the sad outcome of his policies. Many stores remained shuttered, and those that opened up usually had empty shelves. The grocery store we went to felt somewhat like the back shelves of a bodega - stocked, but dusty with only the passed-over items that shoppers tended to disregard.

Though I never felt unsafe in Bulawayo, I was acutely hypersensitive as a white man marching around town with my backpack. Zimbabwe is over 99% black - I don't think I've ever been to a country that was 99% anything. On Easter Sunday, walking the streets, I was a main attraction for curious passerby. Yet somehow I was more at ease here than many places we'd traveled, such as the CBD in Joburg or running along the industrial Yangon River. In its big streets and boarded up shops, Bulawayo felt a lot like southeast Washington DC, where much of DC's 70% African American population was based, and where I worked construction a couple days a week the summer after high school.

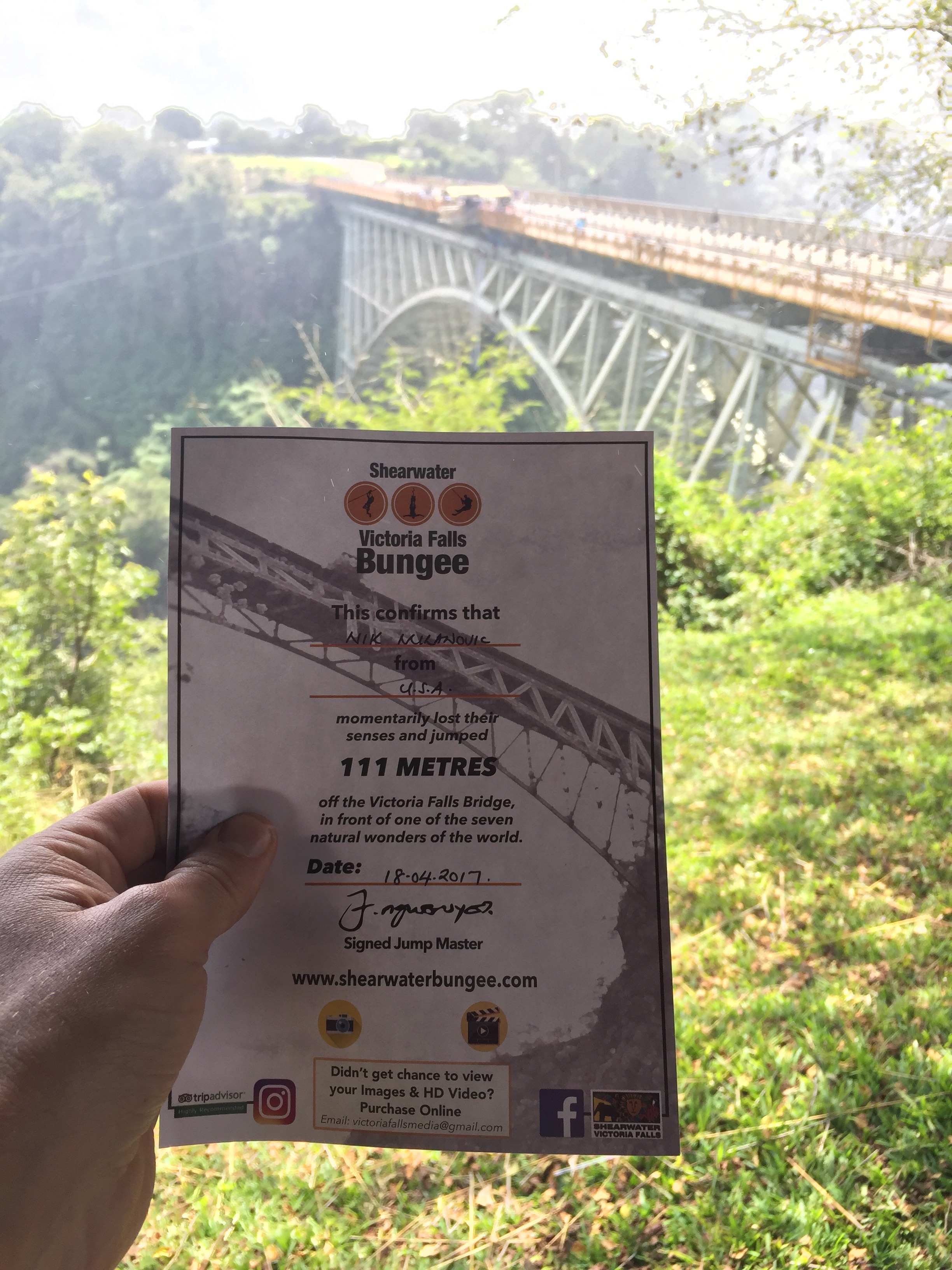

On the overnight train from Bulawayo to Vic Falls I met three girls who were studying in South Africa, two American and one French, also heading to the falls. In South Africa, Dan, Sarah, and I had gone to watch bungee jumpers launch themselves off the world's highest bridge bungee in Storm's River. After some empty boasting back and forth about how we would do it, the three of us chickened out and left without jumping. Knowing there was another jump in front of Vic Falls, one of the seven natural wonders of the world, I was determined not to make the same choice twice. I talked to the girls and we all agreed to jump.

I learned that, in Bulawayo, the girls had been wandering the town looking for a functioning ATM to get enough dollars to pay for the train. Expectedly, all the banks were out of cash and wouldn't get more for a few more days. In these circumstances, people must learn to depend on their families, friends, and communities to get by - much more so than banks and governments. For the girls, that wasn't an option. A local woman, seeing them struggle to find funds, helped them out and then lent them $50 -an unthinkable sum for somebody in Bulawayo.

On the train, I walked up to check out the dining car and met two older men - an off-duty police officer and his friend - who were ecstatic to meet Americans, the first time they had. I told the girls, and the four of us went up to the bar in the next car over. The bartender, an old man sitting on a plastic chair behind the bar, served up South African beer and milk cartons with Zimbabwean home-brew, called Igweba.

The Zimbabweans on board were excitedly friendly at this sight - four white people, much less Americans - on their train drinking their beer with. It made me realize how few tourists really came through Zimbabwe unless they were flying straight in to Victoria Falls. "I love white peoples!" a man named Trusti repeatedly affirmed to us.

Monkeys playing by the train tracks in the morning.

Pulling in to Victoria Falls station.

The train itself is, unsurprisingly, fairly low-budget. Trains in Africa are a world-apart from the ones I took in Thailand (which, by comparison, were astoundingly modern) and even India (which were a bit cleaner.) First class berths guarantee travelers a room with four plastic-cushion beds that dips into freezing temperatures at night as the train moves up the country. We kept the light on to attract all the bugs in the room away from us. Still, we slept soundly through the night and made it to our destination, which is all you can really ask for.

When you wake up in your sleeping car in the morning, children run alongside the train at each village stop, carrying sweet cane to sell and waving to the passengers who lean lazily through the windows. There is no water to wash your face, but you can stand in the doorways between cars and lean out into the wind to wake up. In the first class bathrooms, a sign instructs passengers to press the pedal to let matter out of the toilets. Looking down, you see a chute straight down onto the rail.

Looking down into the gorge of the Zambezi River, south of Vic Falls. The bungee bridge can be seen in the distance in the upper-right corner.

Of course.

Crocodile - not as tasty as anticipated.

Lunch spot on the cliffs over the Zambezi.

Views from the bungee cage at the top of Vic Falls Bridge.

Pauline watches on as people bungee from the Zambia side.

I fall 300+ feet and this is all I get.

One.

Three...

Two.

Bungee!

At Vic Falls, I finally got the chance to bungee jump off the Vic Falls Bridge, which is a 364 foot free-fall. I'd never been bungee jumping before, though I had been skydiving, and I have to say, skydiving was a much less stressful experience. Of the four of us who went together, I made the guides at the bridge send me over the edge first so that I wouldn't have to stand around and watch people jump before me. Once you're in the air, the process is pretty simple: just fall down face-first. The hard part is getting to the edge of the jump. They also charge $150 per jump, which is pretty damn pricey considering that just a couple years ago, a girl did the jump and her bungee cord snapped, sending her into the river. The Zambian government's compensation to her? A free bungee jump next year once the cable was repaired.

"What the hell am I doing?"

The sunset cruise crews.

Across Zim, like most southern African countries, you see women with the same style of swaddling their small children - tying off small blankets or large towels around their waists and wrapping these tightly enough to compress their babies to their backs. Babies seem much less fragile in southern Africa than back home. Mothers pick small children up by the arm and plop them down elsewhere. Babies on cramped, rocking, noisy buses sit easily with a strange tranquility that would seem somehow out of place in the States.

A casual hippo battle off the side of our sunset cruise.

Sunset cruise views along the Zambezi River (which spills into Vic Falls.)

At Vic Falls town, families of wild elephants, warthogs, monkeys, and baboons roam the streets looking for food and wander into the bush next to pedestrians. Elegant hotels and waiters fluent in English cater to married couples on their 25th and 50th wedding anniversaries. The town, which offers $50 booze cruises, $150 safaris, and $300 helicopter rides, is in stark contrast to the rest of the country. Similar to the two separate systems maintained by China for the mainland and Hong Kong, Vic Falls undermines the strong anti-western Mugabe stance that characterizes the 'other' Zimbabwe.

All of Victoria Falls looks like something you would find animated into a Disney Movie.

Zimbabwe surprised me for its hospitality in the face of its poverty. ATM's didn't work, and street touts would turn from selling to begging quickly if they thought passerby weren't interested in their wares. Still, I always felt welcome and safe in Zim because of the warmth of the people there.

Setting off from Vic Falls, I headed to Botswana for a safari followed by a trip to Gaborone, the capital, where I would have to get yet another new emergency passport to augment the lack of open visa pages in the passport I got in Cambodia.

Nik / 4.30.17

Required pic of Uncle Bob in every office, store, home... pretty much everywhere.

One nifty keepsake you can buy from almost anyone in Zimbabwe is their discontinued currency, the Zimbabwean Dollar, which due to hyperinflation was at one point denominated in the hundreds of billions.